One of the many aspects that has a deep impact on those who visit Japan is seeing so many elderly people busy in the most disparate activities. Someone supervises an intersection to ensure the safety of children crossing. Some other sweeps off the leaves on the square in front of a temple. Other people dedicate themselves to taking care of the flowers in the pots that embellish the paths near their condos…

It is not just an issue linked to the aging population or a less than prosperous retirement system. In the Japanese mentality, the concept of retiring, perhaps from job, does not coincide with the idea of ceasing commitment to one or more activities.

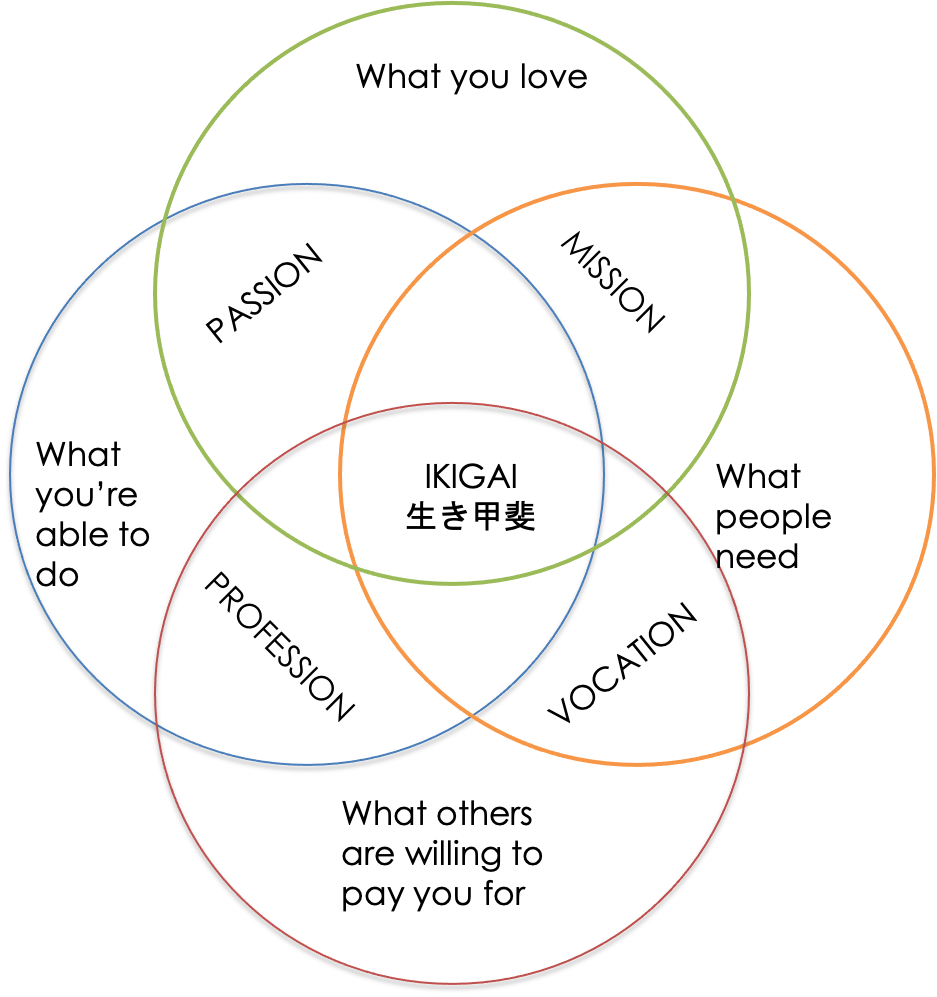

“The happiness of always being busy” can be a good approximation of the literal translation of the term ikigai 生き甲斐, which is broadly translated as a reason for living.

The link between longevity and lifestyle is a topic that attracted many researchers, including Dan Buettner, a National Geographic journalist. His research identified five “blue zones” where the number of centenarians, their health and the quality of their lives suggest that connection is something deep and real.

After his TED talk in Minnesota in 2009, in which the concept was used to explain the phenomenon of longevity in Okinawa, the term ikigai literally conquered the Western world.

A world that objectively struggles to find its own identity and therefore a purpose worth getting out of bed every morning.

To translate into Western culture a concept rooted in the essence of Japanese life, a British consultant, Mark Winn, developed the following diagram:

According to this approach, an activity that balances what we know with what is useful to others; what we love doing with what others are willing to pay us for, would be an activity worth waking up every morning.

An activity that is the convergence of awareness of what we are truly passionate about, which highlights what we are called to achieve in our lives, through a profession.

The emphasis placed on the economic aspect is strong; after all, it is also true that the activity through which each of us provides sustenance for ourselves and others is something that absorbs energy, time and resources for a large part of our lives.

However, there is something more. Work is a predominant but not total part of life. And if ikigai is a principle, it must also apply to any other context.

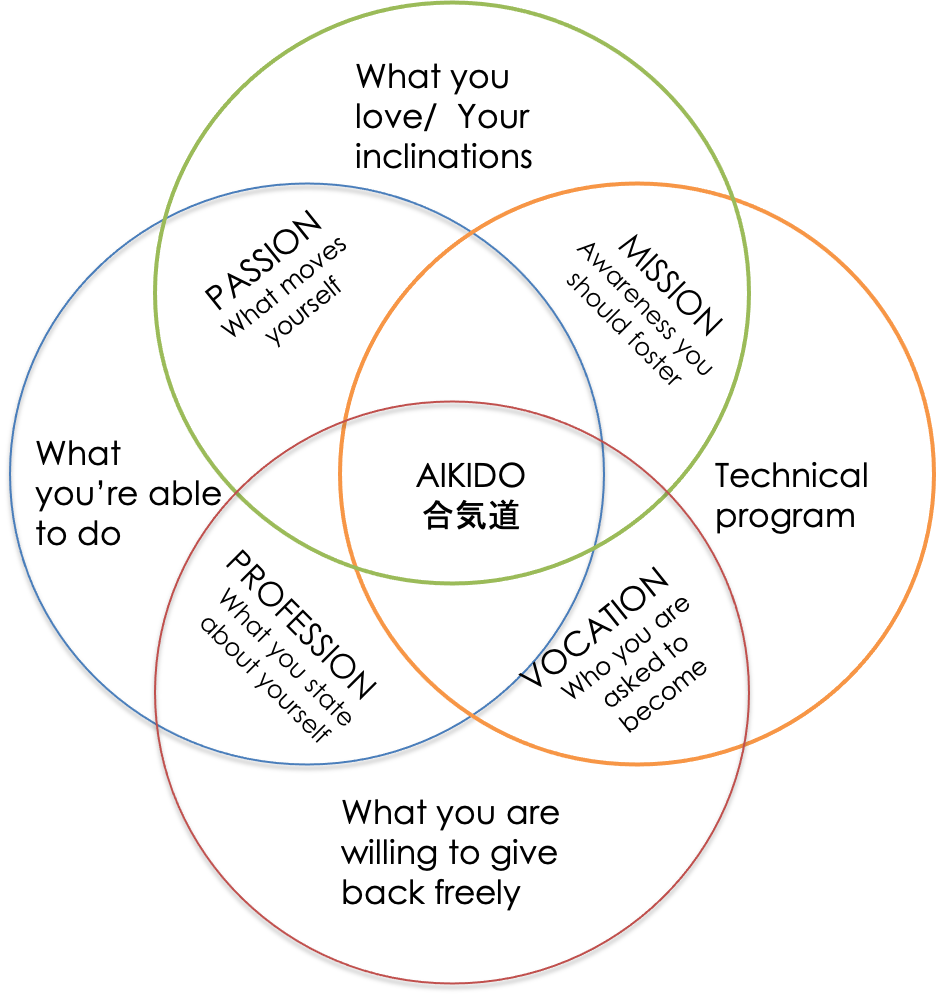

What happens if we apply this scheme to a martial discipline like Aikido? Let’s see together how the scheme is modified:

Each of us steps up on the mat for the first time, bringing with us what he/she can do. There are those who already have well-developed motor skills, there are those who have a good mnemonic learning ability, there are those who know how to patiently dedicate themselves to practice, there are those who have a healthy ambition to improve… The scheme of ikigai applied to Aikido tells us that every practitioner has, from the beginning, skills. Every practitioner is already “good” at something.

On the other hand, the technical program represents a first horizon of what is needed. It is necessary to develop physical and technical skills, which require time and, in the eternal bridge between what we are already capable of doing and what we are not yet able to do is the evolutionary tension in which a discipline is placed, which not surprisingly in Japanese culture identifies itself with the path, the do 道, precisely.

The personal inclinations with which we approach the practice represent a polarity that, over time, gives personalization to the way of practicing. If we love the competitive aspect, the practice will have a very physical dimension. If we love the introspective aspect, the discipline will lead to forms of practice more linked to the discovery of ki 氣. If for us the relational aspect and respect are the priority, the practice will take forms more inclined towards the study of connection.

In the practice of a martial discipline – and given the two cents that make the global turnover of Aikido- it seems unrealistic to talk about “what others are willing to pay for”. Here the Western representation of ikigai falters dangerously. It is necessary to turn the sentence upside down and reintroduce that sense of gratuitousness and giving back to the community to which one belongs which can be seen first-hand when admiring the industriousness that is so moving in elderly Japanese people.

What are we really willing to let go and give back? If we look at our history, just as if we look at an average beginner, we see on the one hand a great enthusiasm but also the embarrassment of not knowing how to orient ourselves at the beginning. Human bubbles, isolated worlds that need time to feel part of a group that walks (or should walk) in the same direction.

What we are passionate about directs the use of what we like and what we are capable of doing. And it’s something dynamic over time. As children we love playing with Lego bricks. As adults we are passionate about making something bigger than a game. It’s not passion that changes, it’s our experience and awareness that, brick by brick, make the game broader. And so it is also in a discipline.

What we love is somehow framed by the grammatical rules of the language we use to express it. This is the real meaning of the technical program. In this way the mission is to explore the technical program, test after test, in order to equip ourselves with a conscious language to express what we love and what we know how to do.

If I am willing to give parts of myself freely and freely to this process, I can better understand what I am called to become. It is generally thought that talking about vocation means talking about renunciations. So, usually, it’s a topic that is often overlooked. We rather prefer to talk about profession, because it seems to be a dimension in which the choice has the winning character of imposing what we want to be in the world. And, in fact, profession literally means “what we say we are”.

All right. Yet, who are we?

A discipline’s declared objective is the progression and development of the human being, in a simultaneously single (the practitioner) and group (the Dojo) dimension. Those who have gone through this path before (the sensei) should be clear that their guidance, through technique, serves to develop in people that level of awareness that distinguishes who we believe (and say) we are from who we really are. This is the meaning of the many frustrations that arise between thinking we are capable of doing something we have understood and not yet knowing how to do it.

Precisely because he/she has been there before us, the sensei sees more clearly what the limits are – attitudinal, character, relational, technical and finally physical – on which we really have to work. Not to become beautiful dolls in his collection but to bring out the best version of us, the one that often hides behind our partial yet absolute positions. Our fears. Those defects that we detest so much that we hate them in others.

By patiently developing the two polarities, active and receptive, in tori and nage/uke, Aikido accustoms the practitioner to understanding where to invest the most energy to become what the individual is not yet and to put at the service of himself and others what he has.

Discovering that we are called to be more empathetic, more focused, more decisive, more compassionate, more true, more active… All this reveals the true identity of our self and is one of the reasons why ikigai is discovered and enhanced by a discipline.

Discovering that our “blue zone”, our reason for being, is not necessarily found in Okinawa, Costa Rica, California, Greece or Sardinia, as researchers say, but that it can be recreated in the square of a tatami, it’s a revolution.

It’s rediscovering that we’re alive.

Disclaimer: picture by Content Pixie from Pexels